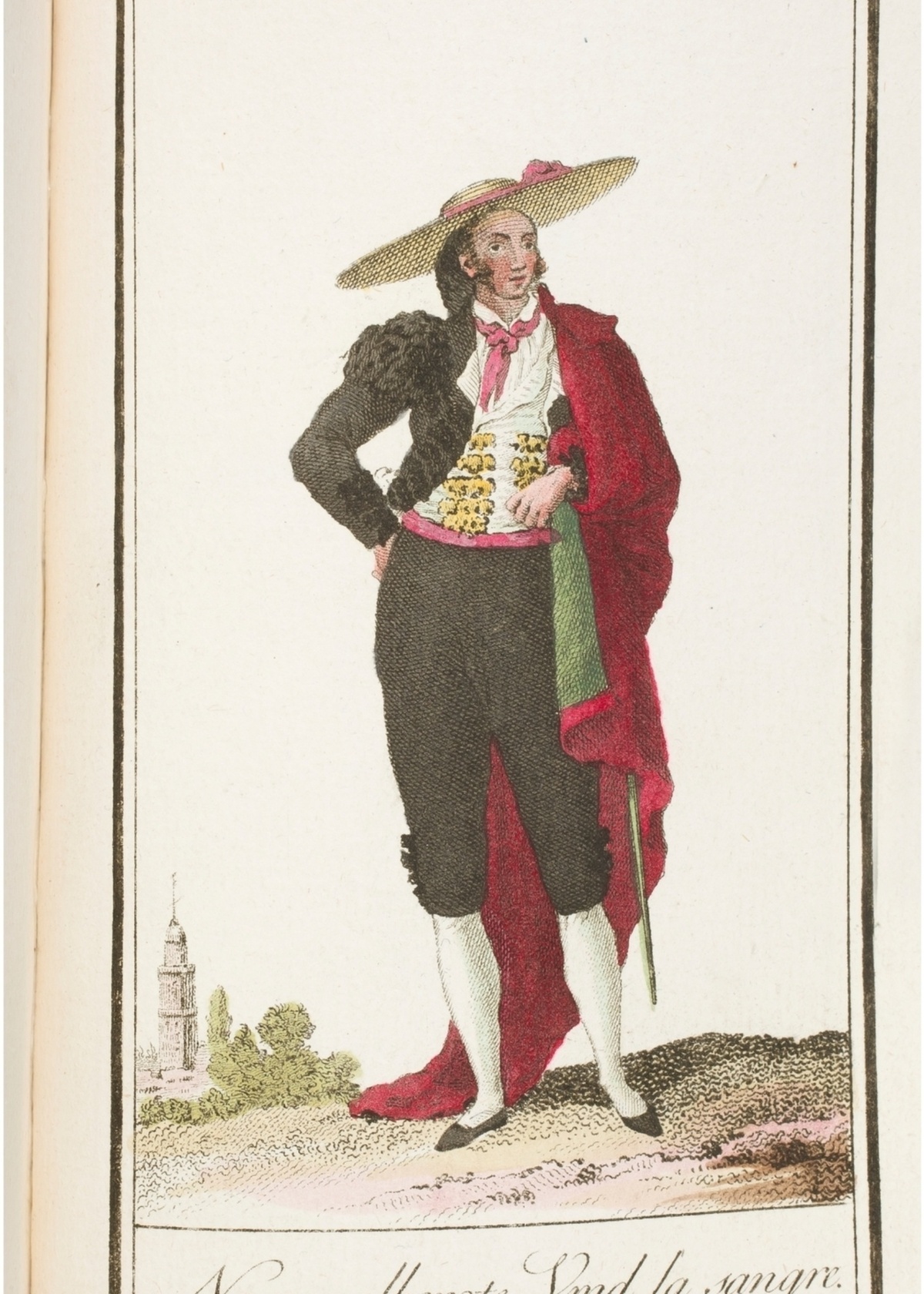

Lord Mountstuart’s Spanish Grandee Dress

Read on to discover the fascinating history behind Lord Mountstuart's Spanish Grandee Dress, which was the research focus for our placement student from the University of Glasgow's Dress and Textile Histories MLitt, Gabriela, when she visited Mount Stuart in 2022.

The enigmatic full-length portrait of John, Lord Mountstuart (1767-1794) c. 1795 – which presides over the Dining room at Mount Stuart – offers a glimpse into the fascinating life and foreign sartorial influences of the young successor.

The Bute Collection fortunately holds the extant garments worn by Lord Mountstuart that are featured in his portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence. The survival and condition of the Spanish Grandee Dress presents a unique and rare opportunity to compare the pictorial clothes with their reality.

The black beaded jacket, silver waistcoat, two pointed caps and the Montera cap are the surviving items that form the Spanish ensemble. Although the portrait reveals several more items that completed his ensemble, such as the black coat and dark blue sash around his waist, their survival is lost. Nonetheless, the remaining items not only offer insight into Lord Mountstuart’s physicality, but also of the Bute Family’s connection to Spain. The Spanish dress and the Lawrence portrait were likely passed down the family line of Lord Mountstuart’s second son, Lord Patrick James Crichton-Stuart.

John Stuart was the first-born son of John, 4th Earl of Bute (later appointed Marquess) and until his abrupt death in 1794 he was preparing to assume his father’s role when the time came. As a young man, Lord Mountstuart set off to travel Europe on his Grand Tour, just as his forefathers had done. His father’s letters reveal that Lord Mountstuart travelled to Spain in 1791, when he likely commissioned the Spanish dress. A relationship between Spain and the Bute family had been previously established – the 4th Earl had been ambassador to Spain in 1783, although in absentia – and this connection may have guided Lord Mountstuart’s experience in Spain.

Upon close observation of the garments, several clues suggest that the items were coordinated and planned – for example, the jacket features a section of the waistcoat’s fabric on the front and interior lapels. Additionally, a pink interior lining is found in the jacket and two of the pointed caps. The jacket and waistcoat also align with men’s fashions of the 1790s, particularly with regards to their structured collars.

What makes Lord Mountstuart’s garments ‘Spanish’ is in their design and iconography. Although Lawrence illustrates El Escorial Palace in the far distance of the portrait, it is in Lord Mountstuart’s dress which truly offers insight into the young man’s affiliation with Spanish culture. The jacket and the three caps are rooted in Spanish folk and regional dress, particularly with the bullfighter. During the 1780s and 1790s, the Spanish aristocracy sought a greater sense of national character and begun sourcing inspiration from the working-class ‘types’, referred to in Spanish as ‘majos’. This was in response to the French style which had dominated the Spanish court since the Bourbon king, Philip V (grandson of Louis XIV) came to the throne in 1700. The influence of majo dress materialised into luxuriously crafted Spanish fashions which was refined through sumptuous, expensive materials similarly found in Lord Mountstuart’s dress — silk, velvet, and silver thread. Several portraits by Francisco de Goya illustrate the impact of the majo style on the dress worn by Spanish Grandees (nobles).

Although the pointed cap Lord Mountstuart wears in the portrait was called ‘hideous’ and his habit ‘strange’ by True Briton in their review of the 1795 Royal Academy exhibition, it’s association to the majo was likely lost or too ‘exotic’ for the British public. Many aspects of Lord Mountstuart’s dress are associated with the Spanish bullfighter – whose uniform was slowly starting to take form. Lawrence illustrates Lord Mountstuart in a stance which echoes the artistic conventions of Spanish portraits of the majo or bullfighter. Lord Mountstuart was likely involved in this process, demonstrating his understanding of how the clothes were worn and celebrated. Specific details in the portrait, such as the outward pointed foot and the position of his arms – with one resting on the hip, and the other nestled below the chest within the coat – mirror the works produced in Spain. Lawrence also positions the coat over the left shoulder – this deliberate sartorial arrangement carries through today in traditional bullfighting ceremonies where the bullfighter will enter the arena with his cape elegantly hung over his left shoulder and wrapped around his waist. The physical garments alongside their pictorial representation also demonstrate how these pieces were worn and what it signalled.

Lord Mountstuart commissioned Thomas Lawrence, the most favoured portraitist during the 1790s, to encapsulate a dramatic and stylish portrait which symbolised the Lord’s place among the Bute family. It is likely that during Lord Mountstuart’s visit to Spain, he bought or commissioned the Spanish dress, and the portrait indicates he would have worn the items during his sittings — suggesting they weren’t only a souvenir, but they were made for Lord Mountstuart to sport. The measurements indicate he was quite narrow, which sort of oppose Lawrence’s emboldened portrait of the Lord, and speaks to the relationship between portraiture, dress, and self-identity.

It is incredible to see the Spanish dress and portrait reunite in the same space – a tangible reminder of Lord Mountstuart’s interest in Spain materialised in both paint and fabric. The Spanish Grandee dress undeniably played a role in capturing his legacy by promoting Lord Mountstuart’s worldly spirit and fashionable taste.