Christmas Dining with the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart

Together with mince pies from our Bakehouse and festive winter greenery from the Mount Stuart Gardens, we have gathered together some of our favourite objects from the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart to set a Christmas tablescape. Join us at the Mount Stuart Dining Table to discover more about festive dining traditions, and read until the end for a special recipe to try this Christmas.

While Christmas dinner may look a little different this year, the tradition of setting the dining table remains a treasured part of the festive season (even if it is just for one). Many of the holiday rituals that we are familiar with today are relatively recent inventions. In fact, Christmas Day only became a national public holiday in Scotland in 1958.

This limited history of Christmas can be traced back to the 1560 Scottish Reformation, when Scotland split from the Catholic Church. All feast and church holidays were discouraged, which included celebrations of Yule or Christmas. This was reinforced by a 1640 Act of Parliament of Scotland further abolishing ‘Yule vacations’.

As it was not possible for Scots to celebrate Christmas, Hogmanay (New Year’s Eve) became the focus of gift-giving and was considered to be the true calendar highlight. It is only in the 1840s that presents began to be exchanged at Christmas rather than New Year. The ‘traditional Christmas’ rituals that we associate with today, are in fact the product of the early nineteenth century industrial and commercial revolution of the Victorian period.

Christmas Cards

The first Christmas card is considered by historians to be that designed by John Calcott Horsley, and commissioned by Sir Henry Cole in 1843. The card features three generations of a middle-class family sitting down for Christmas dinner, and can be seen within the V&A’s collection here. Henry Cole was an educator and inventor, and was the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum). He was heavily involved in reforming the British postal system, and encouraged the use of decorated cards and letterheads as a timesaving solution to unanswered mail.

While Cole’s first published card was considered too expensive to be commercially successful, the advances in the printing process less than two decades later led to the 1860 – 1890 heyday of Victorian Christmas cards. Today, over one billion Christmas cards are bought in the UK each year.

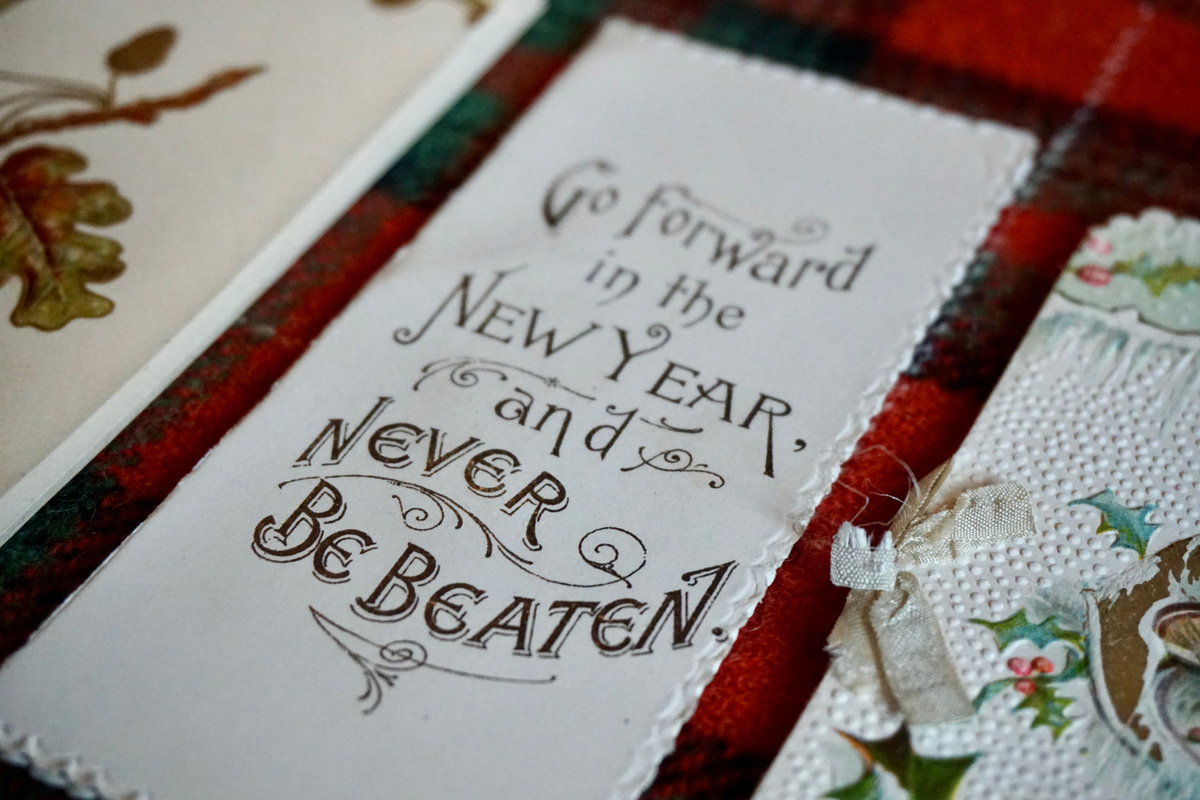

Box 3, The Papers of Lord Colum Crichton-Stuart, The Bute Archive at Mount Stuart

Christmas Cards from the Bute Archive at Mount Stuart

The three Christmas card featured in the image above are a selection saved by Lord Colum Crichton-Stuart (1886 – 1957), whose papers are kept in the Crichton-Stuart family’s Bute Archive at Mount Stuart. Lord Colum was the fourth child of John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute, and Lady Gwendolen, 3rd Marchioness of Bute (née Fitzalan-Howard). Lord Colum married Elizabeth Caroline Hope, and had diverse cultural interests, from learning languages to seeing live theatrical performances. An image of him as Salario in 'The Merchant of Venice' is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

The Christmas cards above are dated between 1908 – 1914, and present a series of happy holiday sentiments. The card on the left features oak leaves and acorns: symbolic of the House of Stuart, and a fitting link to the Crichton-Stuart family. The central card’s uplifting message – ‘Go forward in the New Year and never be beaten’ feels extremely timely and relevant as we approach 2021. The card to the right is a more elaborate embossed design, and displays the intricate Victorian print culture innovation of die-cut paper edges.

Greenery & Decorations

A selection of evergreens and berries has been gathered by Dot from our wonderful Gardens at Mount Stuart to create a festive atmosphere. This tradition of decorating houses with winter greenery can be traced back to classical mythology. As evergreens maintain their colour and vibrancy throughout the cold winter months, they were regarded as a symbol of life and heralded the promise of spring. In Georgian Britain, evergreens were only brought into the home on Christmas Eve, as it was considered unlucky to bring it indoors before this date. After Twelfth Night (6th of January), all the greenery was removed and burned to avoid any further bad luck.

Holly and ivy have similarly been long associated with winter solstice and pagan customs, and mistletoe is linked to both Druid and Norse mythology. Imagery of holly and mistletoe made a reappearance on Christmas cards in the mid-nineteenth century, and has remained a popular symbol of the season ever since.

collection of English and Irish silver animal figures in the Bute Collection at Mount Stuart.

The friendly behaviour and migration patterns of the robin has marked this species as the nation’s favourite bird. While the robin lives in the UK year-round, its numbers are bolstered during the winter months, when birds who have migrated from the cold of northern Europe join our domestic residents. British robins also tend to prefer gardens rather than their European counterpart’s woodland habitat, as they are able to follow the progress of a gardener’s work closely, with the digging and turning of the soil revealing worms for feeding. Their popularity is due in part to their bold nature and cheerful song. When there is a snowfall and the robin’s usual food sources are covered, they have been known to bravely perch on hands for feeding. They are also one of the few songbirds that sing all year round, with an early dawn chorus and one of the last birds to stop on a winter evening.

Robins’ association with Christmas imagery is said to be traced back to the Victorian period. During the late nineteenth century, Royal Mail postmen wore red uniforms, which earned them the nickname of ‘robins’. As the tradition of exchanging Christmas cards between friends and family swelled in popularity, images of postmen in their red jackets delivering post were illustrated on cards. Soon, this nickname for the postman was translated to depictions of actual robins themselves holding cards in their beaks. Robins have continued to be a popular Christmas symbol ever since the Victorian era, and there is perhaps no other bird as closely associated with the British winter as the robin.

Christmas Dinner

While Christmas feasts have occurred since the medieval period, the traditional family Christmas dinner as we understand it today was only popularised in the mid-nineteenth century.

A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens was first published in 1843, and was immediately successful with both the public and critics – all 6,000 copies printed were sold out by Christmas Eve of that same year. The Cratchit dinner featured within Dickens’s work helped popularise the classic English Christmas menu, while also emphasising the themes of family and goodwill at Christmas. A turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, gravy, plum puddings, mince pies and oranges all feature within the novella. These menu selections resonated strongly both with British and American audiences. The choice of a turkey in particular proved to be more accessible than the beef or venison previously associated with aristocratic feasts, as the bird was the perfect size for the typical household.

The Victorian era also saw the introduction of two and three course meals. In both affluent and middle class families, there was also a shift away from dining service la française (serving multiple dishes of a meal at the same time) towards the hierarchical, modern menus that culminate in a single roast.

The William Burges Bute Cutlery Set

The cutlery set featured on the Mount Stuart tablespace was made for John Crichton-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Bute (1847 - 1900), during this period of evolution of Victorian dining rituals. The set was designed by William Burges and made by Barkentin & Krall, a London (Regent Street) goldsmiths that was active from c.1868 – 1930. The firm was founded through a partnership between Danish metalworker Jes Barkentin and German silversmith Carl Krall. They produced several silver objects for Burges, and other designer-architects (including G.F. Bodley and Dante Gabriel Rossetti).

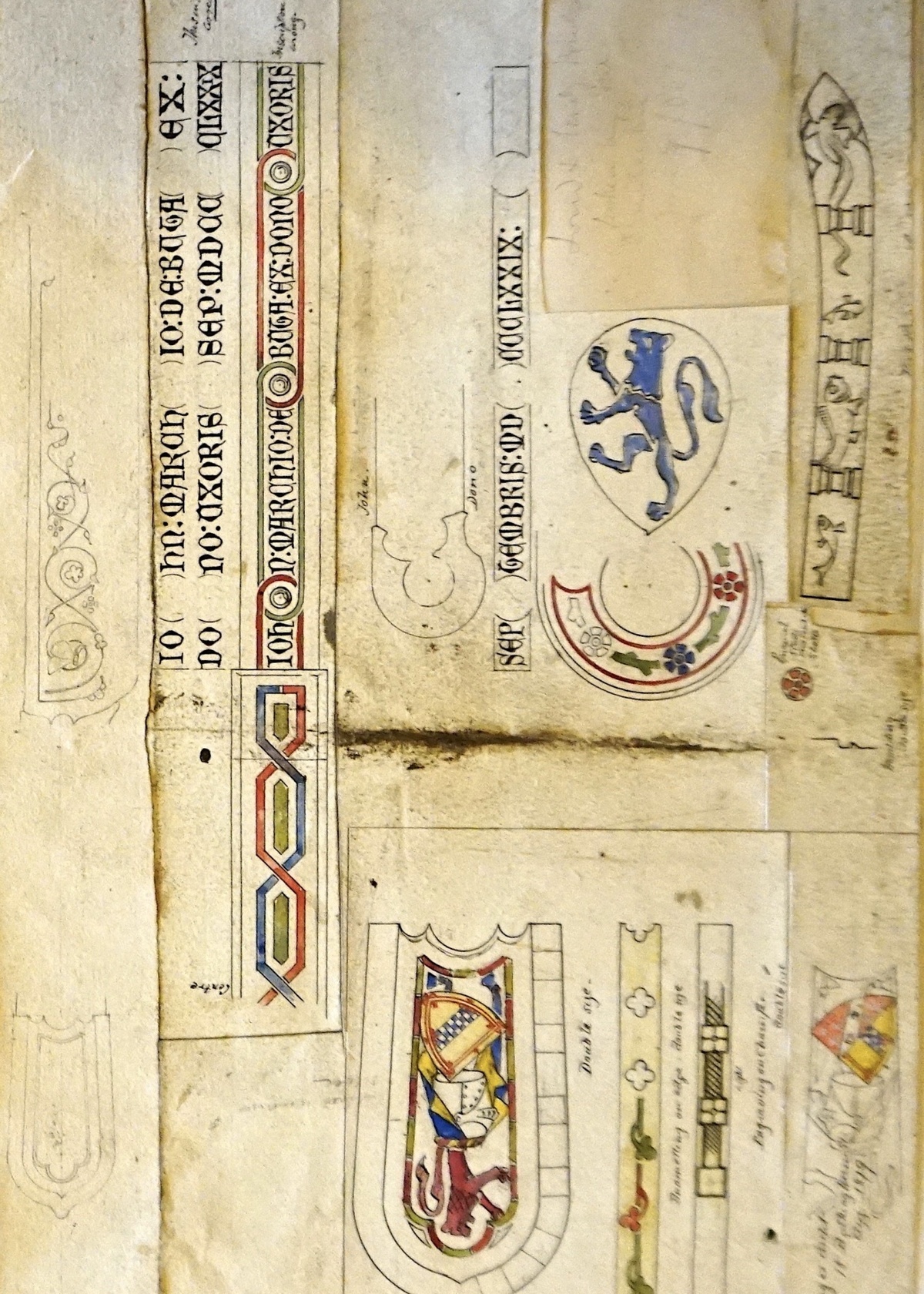

The cutlery set contains a silver, mother-of-pearl and enamel fish-knife and fish-fork; a silver-gilt, ebonised and enamel knife and fork, and a silver-gilt turtle soup-spoon. The original design of the remarkable cutlery set by William Burges is preserved by the Bute Archive at Mount Stuart, and can be seen in the image above (catalogue reference: WB/1/17).

Image: burges cutlery closeup – MST Christmas: The William Burges Soup Spoon, The Bute Collection at Mount Stuart

Pudding & Mince Pies

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the main meal was traditionally followed by a variety of sweet desserts. A Christmas pudding, or plum pudding was primarily made from dried prunes and plums. Mince pies have also been popular since the Tudor period, though their exclusive association with the Christmas holiday season came much later - as did their sweet nature. Recipes for mince pies from the nineteenth century still frequently included meat alongside sweet ingredients and spices, and it is difficult to know exactly when meat was dropped from mince. Nevertheless, these tasty treats continue to delight, many generations after they were first conceived.

This Christmas, we are delighted to also be able to share a special recipe from our marvellous Mount Stuart Bakehouse team, Campbell and Carrie. Campbell created the delicious Frangipane Mince Pies featured in our Christmas Dining tablescape, and we are thrilled to be able to bring a little of their bakery magic to your kitchens this festive season.

Mount Stuart Bakehouse’s Frangipane Mince Pie Recipe

Mincemeat:

INGREDIENTS

- 100g currants

- 100g raisins

- 100g sultanas

- 50g dried cranberries

- 50g mixed peel

- 1 small cooking apple, peeled, cored and finely chopped

- 125g butter, cut into cubes

- 50g whole blanched almonds, roughly chopped

- 115g light muscovado sugar

- ½ tsp ground cinnamon

- ½ tsp mixed spice

- finely grated rind and juice of 1 orange

- 100ml brandy, rum or sherry

INSTRUCTIONS

- Measure all of the ingredients (except the alcohol) into a large pan. Heat gently, allowing the butter to melt, then simmer very gently, stirring occasionally, for about 10 minutes.

- Allow the mixture to cool completely then stir in the brandy, rum or sherry.

- Spoon the mincemeat into sterilized jam jars, seal tightly, label and store in a cool place.

Frangipane

INGREDIENTS

- 50g/8oz jam

- 50g butter, softened

- 50g caster sugar

- 1 vanilla pod, split and seeds scraped out

- 1 free-range eggs

- 1 dessert spoonful of plain flour

- 50g ground almonds

- ½ tsp amaretto or almond extract

- + Short crust pastry

- + Flaked almonds

For the pastry, use sweet crust pastry or buy a good quality sweet pastry cases... although homemade are always recommended!

INSTRUCTIONS

- Cream butter, sugar and vanilla together until pale and fluffy.

- Beat in the eggs. Fold in the ground almonds

- Line a muffin tin with short crust pastry circles

- Add 1 heaped teaspoon of mincemeat, top with some frangipane and a few flaked almonds

- Bake in a moderate oven for 15 minutes.

This will keep in an airtight container for up to a week in the fridge.

From all of us at the Mount Stuart Trust, we wish you a very Merry Christmas and a bright 2021.